Sitting on the park bench, overlooking the Allegheny river, he smoked a cheap cigarette. The cheap cigarette no longer seemed so cheap to him, after all he was a man who had lost everything.

He remembered how it had felt like on that day, the scream of adrenaline and the rush of fans. They had jogged out onto the field and into the light. Nothing had ever felt so good, he felt like god, like a hero, like a pawn who would be devoured if he messed up this opportunity. Now he was standing in front of the audience, looking up, bowing down. GOAL!

He was a star now. Every team in America wanted him. He was holding out for Europe, for greater glory, for all-consuming stardom. His agent was busy, good. Truth be told, football bored him now, fame and glory were what kept him going. He was earning a lot now, also managing to spend most of it and more. He still practiced as hard as ever and his game had only been improving. He had played a brilliant season, as a scorer as well as a play-maker. His contract with the zolos was up and his agent was amidst negotiations with a European club. Even though he was a star in America, he was relatively obscure when it came to the world stage. All that would change soon. His life’s dreams were coming true. He was only 19, having left school at 16 to play for his local Pittsburgh club. Now he was leaving the Philadelphia Union after only 2 years.

Years later, his dreams were all true.

Now, he remembered last month. He was panting. He saw black spots. These young f**kers would be the death of him. He was old at 27. The sun thrashed down, some things you can never get used to. Zevon had tasted enough wet salt for one day. He signaled his coach, he was off. He got into his one-of-a-kind Ferrari and drove, but not like the wind. It had happened then. A boy, probably a fan, ran out into the road asking him to stop. Swerve, Squeal, Scream, Smash. Memento Mori.

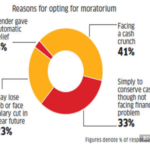

A week later, he was in bed. He had been anesthetized, yet the pain was unbearable. Most of his property had been foreclosed. His investments over the years were all bad, very bad. The banks had moved in like cannibals as soon as they had heard, no more contracts. So he was left there lying on his back, lights off. All that he had left, was the wedding ring on his finger, the buzz in his heart, and the person still by his side.

He looked over the Allegheny river, from a bench made for two.

Aaryaman Aashind.

Calcutta.

eh; what’s that?

a comprehension test?

Excellent read, Aashind

Never knew you write so well. 🙂

it ‘s all greek to me